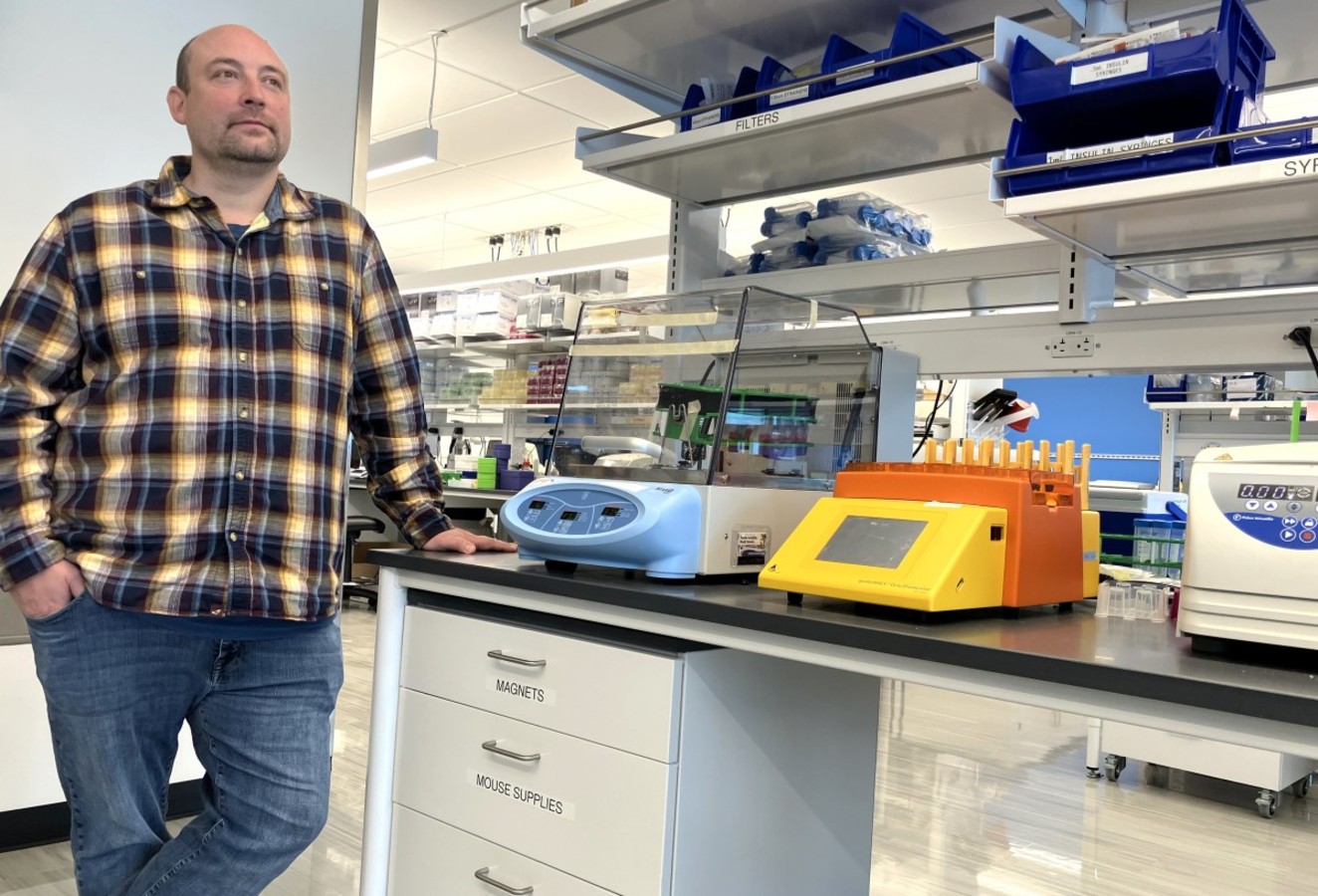

Dr. Mark Headley: 'This has become my lab’s driving interest'

Dr. Mark Headley: 'This has become my lab’s driving interest'

BBI’s Dr. Mark Headley has devoted his career to battling what he calls “an assault from within.”

This “assault” is not domestic terrorism, as one might expect, but rather the metastatic spread to the lungs from other parts of the body, causing cancer cells to colonize, develop, and, without successful treatment, potentially lead to premature death.

Headley, an assistant professor in the Immunology Clinical Research Division, at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, was the corresponding author on a paper in the journal Cell Reports last June, “Uptake of tumor-derived microparticles induces metabolic reprogramming of macrophages in the early metastatic lung.” That paper – written in collaboration with colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco – was built off the initial findings from a paper published in Nature in 2016, “Visualization of immediate immune responses to pioneer metastatic cells in the lung.” Headley was the lead author on that one.

And, as one might expect, Headley is now working on the next peer-reviewed paper on the topic.

“This has become my lab’s driving interest,” said Headley, 41. “We split our time between the basic function of the immune system in the lung and applying that to diseases, such as cancer metastasis – how the underlying immune environment of the lung can alter the course of metastatic disease.”

That “driving interest” is defined by reviewing the first few sentences of the introduction to the study in Cell Reports.

“(T)he mechanisms by which cancer cells disseminate from the primary tumor and successfully colonize distant organs remains largely unknown. Accumulating evidence demonstrates a pivotal role for immune cells in priming distant organs by creating a ‘’pre-metastatic niche’’ that supports the colonization and outgrowth of future incoming cancer cells.”

The key players in these “niches” are macrophages (Greek for “large eaters”), white blood cells that usually surround and “eat” cancer cells’ unique flavors of which have developed as a result of the metastatic spread of cancer from other parts of the body.

"There is much we do not know. We’re still learning how macrophages fit into this puzzle.”

“The essential question is, ‘Do macrophages get bigger and hungrier, or are there changes in how they see and react to the tumor cells?’” Headley said. “In different contexts macrophages can produce different signals and change the way one’s biology operates. In cancer patients we generally see that this process makes macrophages more effective at supporting cancer, becoming a ‘better ally’ for the cancer. However, in this study we found the opposite, macrophages which have eaten tumors appear to be better at suppressing metastasis. There is much we do not know. We’re still learning how macrophages fit into this puzzle.”

How has Headley come to this point of piecing this puzzle together?

He started studying the lung as an undergraduate at Boise State University from which he graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in biology in 2004. One year later, he completed a Master’s Degree in biology, also at Boise State, and subsequently finished a Ph.D in immunology from the University of Washington in 2010.

But it was his work as a postdoctoral fellow working with Dr. Steven Ziegler at the Benaroya Research Institute in 2011, examining the underlying processes of asthma, and how respiratory viruses influence asthma, that “lit the passion in me” about the immune system of the lung.

“At that time, I was not very aware of what I study now – elements of cancer metastasis and the importance of the lung,” he said. “But I was aware of how little we understood of the immune system of the lung, despite the excellent work by others.”

Among those conducting that excellent work was Dr. Matthew Krummel in the Department of Pathology at UCSF. Krummel had studied under Dr. Jim Allison, winner of the Nobel Prize in 2018 for his work using the immune system to treat cancer.

“Max (Headley’s nickname for Krummel) and his colleagues at UCSF were doing amazing work on cancer,” Headley said. “They developed the first studies using microscopy to study live lungs. Being in this group got me thinking about cancer as an immunologic disease.”

After six years in Krummel’s lab, in 2018, he joined the Hutch as an assistant professor in the Clinical Research Division and the UW’s Department of Immunology in the School of Medicine as an affiliate assistant professor.

It’s a safe bet, Headley will devote much of his career as a researcher to studying lung metastasis.

“A lot of what we think about in the lung are viruses coming into it from outside world, such as COVID-19 and other viral diseases,” he said. “But this is different. This is an assault from within.”